My first post in this series observed that climate scenarios omit potentially significant risks. But what if this wasn’t the case?

First, let’s distinguish between physical risks (the risks that arise from the climate actually changing) and transition risks (the risks that arise from policy responses, which may attempt to halt climate change). Transition risks to asset portfolios are already relatively widely appreciated and well-understood across the pensions and insurance sectors. It’s perhaps therefore more important to focus on physical risks.

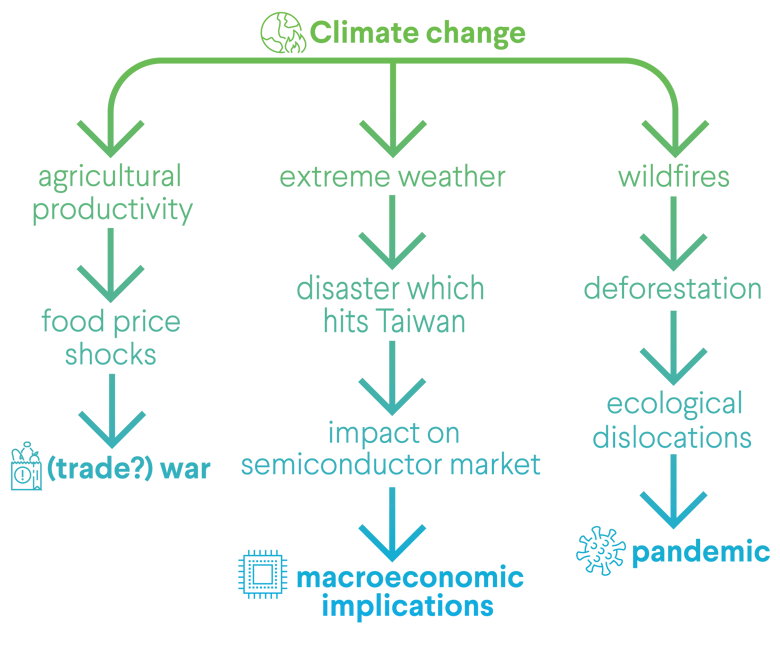

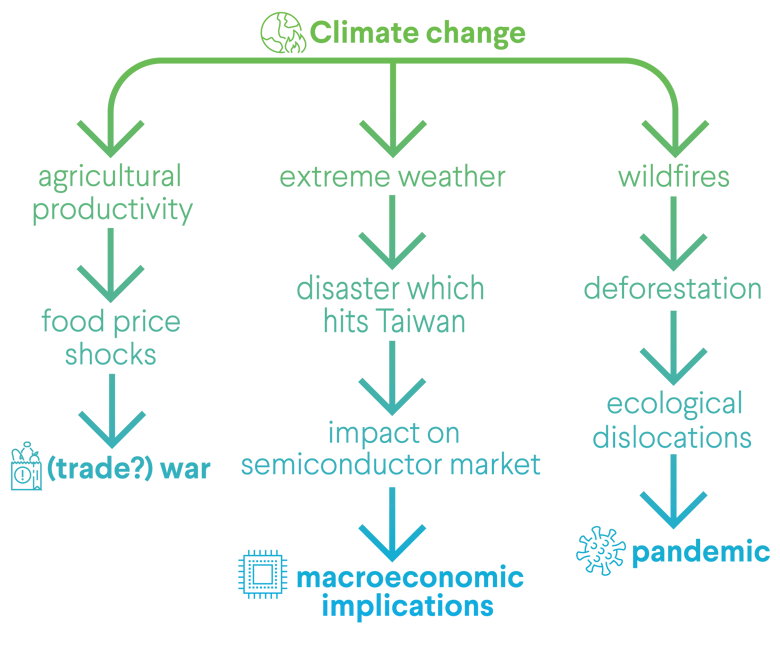

In particular, we need to consider how environmental impacts may be transmitted into economic and financial systems. Here are a few examples of such scenarios:

Although not intended to be comprehensive, these examples can help stakeholders understand how climate change could interact with the financial system in non-obvious ways. Being aware of these implications can help us develop better climate scenarios:

Whilst technical experts may appreciate many subtle details of the way that models are constructed, and may feel tempted to define scenarios based on these details, we believe there is merit in developing more concrete narratives outlining a series of events which could actually occur in the real world. From this, we can consider how those affect the balance sheet of an insurance company or pension scheme. This is likely to be more meaningful to decision makers.

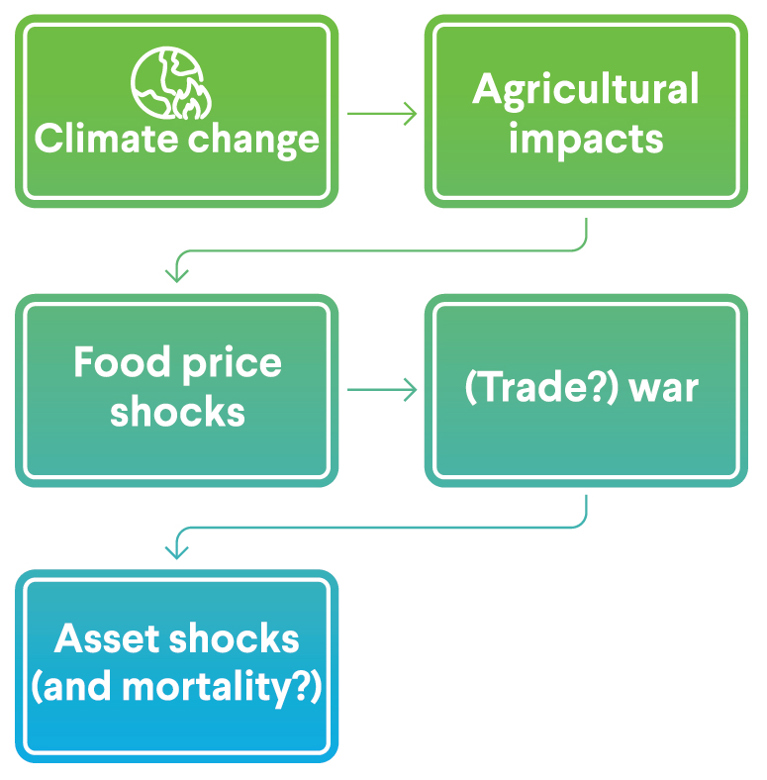

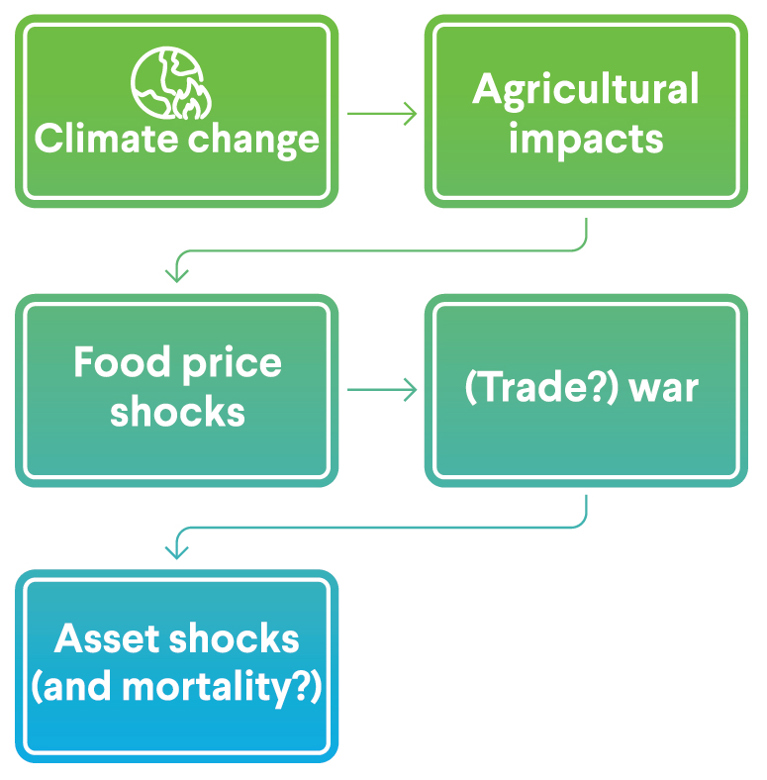

Let’s expand one of the examples set out above and explore some of the ways in which climate change could interact with food and agricultural systems. These are all possible impacts:

- Gradual climate change could be less favourable to some crops in some contexts, for example through changed temperature or impacts on water availability.

- Climate change could lead to extreme weather events, which could harm crop production.

- Climate change could increase the susceptibility of crops to pathogens.

Reductions in crop harvests could have material implications for food prices. For example, in the 2007-8 food crisis, production declined by a few percentage points, and mostly not much more than around 10%. However, some crops had substantial increases – in some cases doublings – of prices. This can be driven by speculation or by other market dynamics.

It is therefore reasonable to expect that climate change could make these scenarios not only more likely in the future, but potentially more severe than similar scenarios which have occurred in the past. For example, we believe this scenario would likely be a driver of inflation, which could drive interest rates up. It would likely also be a driver of geopolitical tensions creating secondary impacts.

If we imagined that a severe food price crisis such as this had occurred, it seems likely that some sort of protectionism could follow. Democracies and even non-democracies are typically averse to having a population which cannot adequately feed itself. We can hypothesise the potential consequences by noting that:

- Net exports have tended to constitute around 30% of GDP in the UK in recent years. Institutional investors tend to invest in companies that are relatively large, and therefore more exposed to the importance of international trade.

- The S&P500 reacted negatively (several percentage points decline) to the threat of US-China trade tensions in around 2018-19.

- One of the inflationary drivers in 2022 is food-related, partly because the situation in Ukraine has constrained the food supply, and partly because of other recent shocks to food production.

The exact decrease in asset values caused by this scenario would depend on the specific assumptions. However, it is not unreasonable to imagine a shock which would compete with the Solvency II Standard Formula stress of 39% decline in equities for a 1-in-200-year event.

A 1-year decline of this severity would already look substantially more severe than most climate scenario models used in pensions and insurance today. And this considers just one plausible way in which climate change could interact with the wider world (food shocks), ignoring the other scenarios we have imagined. Further, because climate change exacerbates the risks of multiple types of severe event, we could see a scenario like this happening alongside other extreme events, which could have hard-to-predict interaction effects.

Developing these specific narrative scenarios could help a financial institution in several ways. First it could act as a calibration tool for a stochastic model, helping to highlight if the variance in the stochastic model is wide enough to account for the scenarios considered. But second, and perhaps more importantly, it can be a good risk management exercise for the leadership team of an insurance company or the trustees of a pension scheme.

Climate change is a complex topic for decision makers to grapple with, but by exploring potential real world outcomes that may arise through scenarios which are more likely as a result of climate change, but are also not specific to climate change, decision makers can gain value from climate scenario analysis.

If you'd like to discuss this further, please get in touch.